by John Holbrook Jr.

A Biblical View, Blog #018 posted November 14, 2016, edited March 9, 2021.

Most versions of ancient chronology put the 18th Dynasty of Egypt in the 2nd millennium BC – specifically c.1550-1320 BC. My chronology, however, which takes the Bible as its point of departure, but which also owes much to Immanuel Velikovsky, puts it almost entirely in the 1st millennium BC – specifically c.1041-812 BC [1] – a period roughly coincident with the Mycenaean or Heroic Age in Greece (c.1008-754 BC).

Despite its fame, the last portion of the 18th Dynasty, which began with the death of Amenhotep III, is shrouded in mystery. When he was killed, his wife Queen Tiy assumed the throne and ruled for eight years. During this time her chief advisor was her brother Ay. Suddenly Akhnaton succeeded to the throne.

In Oedipus and Akhnaton, [2] a brilliant piece of detective work, Dr. Immanuel Velikovsky established to my – and many others’ – satisfaction that the events at the end of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty had provided the basis and inspiration for the Greek tales concerning Oedipus and his family. Velikovsky made the following identifications: Akhnaton was known to the Greeks as Oedipus;[3] his mother Queen Tiy, as Jocasta; her brother Ay, as Creon; Akhnaton’s son Smenkhare, as Polyneices; his son Tutankhamen, as Eteocles; and his daughters Meritaten and Beketaten, Antigone (the two sisters were conflated in the Greek tales). Thus, Velikovsky argued, the Greek tales can provide details in the drama that occurred in the court of ancient Egypt.

The trouble started with Akhnaton. He was a strange figure, and he played the central role in this drama.

Akhnaton was born with some unusual deformities – a thin torso and markedly swollen legs. Velikovsky surmised that these deformities were probably due to progressive lipodystrophy, a rare affliction that causes the elimination of subcutaneous fat in the upper body and the accumulation of adipose tissue in the lower body.

Egyptian history is silent concerning Akhnaton’s origins. Fortunately, the Greek tales are not. They indicate that, probably due to his deformity, he was abandoned in the wilderness as a baby, but was saved by a shepherd, who conveyed him to Mitanni, where he was raised in the royal household.

After the death of his father in 861 BC, Akhnaton appeared out of nowhere and married Queen Tiy, apparently unaware that she was his mother. The Greek tales supply a mechanism for this stunning elevation to the throne of Thebes: he solved the riddle of the Sphinx.

During his reign, Akhnaton demonstrated intense hostility toward both the priests in Thebes and the memory of his father. He destroyed the Theban Oracle, defaced statues of his father, and assumed his father’s name, Amenophis, which was the cultural equivalent of patricide.

Akhnaton maintained an aberrant household. His first wife appears to have been Nefertete, who was the daughter of Ay and Ty, whom he probably married before becoming pharaoh, and with whom he sired Tutankhamen, Ankhesenpaaten (eventually the wife of Tutankhamen), Meketaten, Meritaten (eventually the wife of Smenkhare), and three other daughters. His second wife was Queen Tiy, whom he married as he became pharaoh and with whom he sired Smenkhare and Beketaten (his favorite). A few years later, Tiy supplanted Nefertete as his chief wife, but then disappeared from the royal annals in his regnal year 13 (848 BC). She does not appear to have been buried in the tomb which was built for her. The Greek tales indicate that she committed suicide and was denied a proper burial. His third wife was Tadukhipa, who was the daughter of the King of Mitanni. She was sent by her father to be a wife to Amenhotep III, but arrived after he died, during the reign of Queen Tiy. She lived in the royal harem and became available to Akhnaton when he ascended to the throne.

In his year 4 (857 BC), much to the horror of the priests in Thebes, with whom Ay sided, Akhnaton formally rejected the gods of Egypt, and established the monotheistic cult of Aten.[4]

Akhnaton then built a new city at El Amarna, which he named Akhet-Aton. It was dedicated to the worship of Aten. In his year 5 (856 BC), he moved the royal court from Thebes to Akhet-Aton

In his year 6 (855 BC) Egypt was inflicted by a plague or some other affliction, which caused the oracles to maintain that an unacknowledged and un-atoned for patricide existed in the land. The oracles regular insistence on this interpretation of the disturbance caused Akhnaton to commence searching for the criminal in question, and his investigation eventually led to himself.

Meanwhile, Akhnaton flaunted his deformities by appearing nearly nude in public, maintaining that they indicated he was divine and had been divinely elected to rule Egypt. At an unknown point, however, consumed with guilt and opposed by many for his bizarre behavior, he became blind – possibly by his own hand. At that point, his physical condition matched his spiritual condition.

In his year 16 (845 BC), Akhnaton retired from public life and lived as a semi-prisoner in the palace while his son and co-regent ruled the land.

In year 20 of his reign (841 BC), Akhnaton was officially deposed and driven into exile for unknown reasons, accompanied by his devoted daughter Beketaten. Thus, he disappeared from Egyptian history.

Upon Akhnaton’s deposition, a rivalry between his two sons Smenkhare and Tutankhamen immediately surfaced, undoubtedly nurtured by their uncle Ay, who brokered an agreement between them that the two brothers would occupy the throne of Egypt on alternate years.

The elder Smenkhare went first and reigned for one year (841-840 BC). During his reign, Akhet-Aton was abandoned and the government returned to Thebes (archaeologists estimate that Akhet-Aton was inhabited for 15 years, which would place its abandonment in 841 BC, immediately after Akhnaton’s deposal and in Smenkhare’s year 0. At the end of that year, Smenkhare turned the throne over to his brother Tutankhamen in accordance with the agreement between them.

Tutankhamen ruled Egypt for 8 years (840-832 BC). At the end of his first year, he was supposed to return the throne to his brother in accordance with the agreement between them, but he failed to do so. Instead he sought his brother’s death – undoubtedly due to the influence of his great uncle Ay. Smenkhare fled to Greece, where he stayed with King Adrastus of Sicyon and married Adrastus’s daughter Argeia.

In order to reinstate his son-in-law on the Egyptian throne, King Adrastus undertook the 1st Theban War (832-831 BC) (also known as the Seven Against Thebes). He raised an army from the cities of the Peloponnesus, invaded Egypt, and besieged Thebes. The war was a debacle for the Greeks. Most of the Greek heroes were killed. Both Smenkhare/Polyneices and Tutankhamen/Eteocles were killed; they fell in mortal combat with one another.

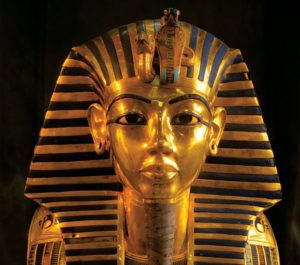

On the death of the two legitimate heirs to the throne, Ay, who had harbored designs on the throne for years, seized it and ruled Egypt for 12 years (832-820 BC). He immediately issued two commands: (a) that Tutankhamen/Eteocles be buried in the traditional manner for royal figures (the photograph below shows a sample of the splendid artifacts that were crowded into his tomb) and (b) that Smenkare/Polynices be left to rot on the battlefield.

Disregarding Ay’s decree concerning Smenkhare, his wife Meritaten (Antigone) buried him ritually by sprinkling dust on his body as it lay where it had fallen on the battlefield, for which she was condemned by Ay to spend the rest of her life in a small pit immediately outside Queen Tiy’s tomb, where Smenkhare was laid to rest.

In Ay’s year 11 (821 BC), King Adrastus invaded Egypt and besieged Thebes again in what became known as the 2nd Theban War (821-820 BC) or the War of the Epigoni, who were the sons of the dead heroes of the 1st Theban War. The Greeks undertook the war to avenge the dead heroes and install Thersander, the son of Polyneices and Argeia, on the Egyptian throne. This time the Greeks enjoyed a measure of success. Some historians claim that they invested the city, deposed Ay, and installed Thersander on the Theban throne. I agree with them. According to my chronology, Ay was followed by Armaeus or Armais, who, I believe, was Thersander. He ruled for seven years (820-813 BC) and was succeeded by his son Ramesse, who ruled for one year (813-812 BC). Then Egypt was invaded and conquered by the Libyans.

So ended a royal dynasty riddled with betrayal, blasphemy, deceit, incest, idolatry, intrigue, and self-aggrandizement.

_____________________________________________________

[1] According to my chronology, the pharaohs of Egypt’s 18th Dynsasty reigned as follows: Ahmose, who assisted Saul in destroying the Hyksos/Amalekite fortress Avaris at El Arish, reigned for 25 years (1041-1016 BC); Amenhotep I reigned for 13 years (1016-1003 BC); Thutmose I reigned for 21 years (1003-982 BC); Queen Hatshepsut, who was known in the Bible as the Queen of Sheba and visited Solomon in Jerusalem, reigned for 35 years (982-947 BC); Thutmose III, who was known in the Bible as Shishak and sacked Jerusalem and its Temple, reigned for 32 years (947-915 BC); Amenhotep II reigned for 15 years (915-890 BC); Amenhotep III reigned for 21 years (890-869 BC): Queen Tiy, who was Amenhotep III’s wife, reigned for 8 years (869-861, Akhnaton, who was the son of Amenhotep III and Tiy, reigned for 20 years (861-841 BC); Smenkhare, who was Akhnaton’s eldest son, reigned for 1 year (841-840 BC); Tutankhamen, who was one of Akhnaton’s younger sons, reigned for 8 years (840-832 BC); Ay who was Queen Tiy’s brother and Akhnaton’s uncle, reigned for 12 years (832-820 BC); Armaeus or Armais, who was Smenkhare’s son, ruled for 7 years (820-813 BC); and Ramesse, who was Armaeus’s son, reigned for 1 year (813-812 BC).

[2] Velikovsky, Immanuel, Oedipus and Akhnaton, Doubleday & Company, Garden City NY, 1961. I highly recommend it. It is a tour de force.

[3] Akhnaton was also known to the Greek historian Herodotus as Anysis.

[4] Some people assert that the cult of Aten was the first monotheistic religion. A little thought will undercut that assertion. The cult of Aten (est. c. 857 BC) was preceded by the Adamic religion (est. 3977 BC), the Noachic religion (est. 2321 BC), the Abrahamic religion (est. 1894 BC), and the Mosaic religion (est. 1464 BC), all of which were monotheistic and focused on the God of the Bible who created the heavens and the earth.

© 2016 John Holbrook Jr.